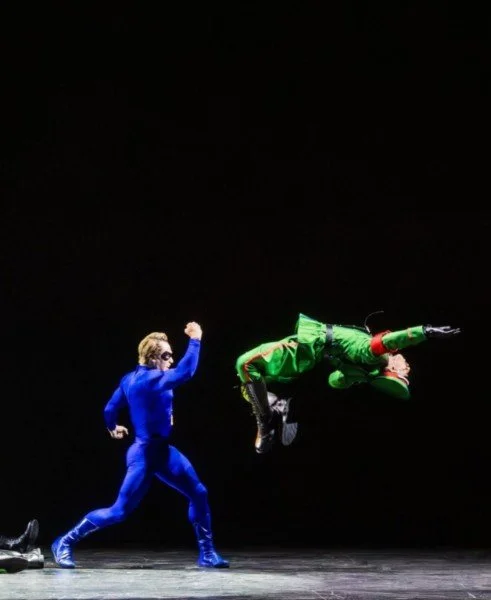

Jerimy Rivera as The Escapist knocking me out.

The pant legs give none as I squat to show the confused dresser in the quick change.

“They gave me the gusset but it’s not quite enough,” I say. “Granted, I don’t do anything that requires me to stretch.”

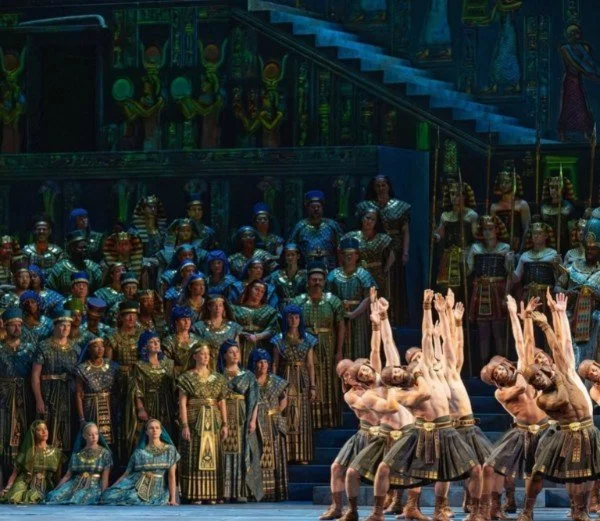

Not entirely true. Embodying a Nazi on the Metropolitan Opera stage in a moment that enlivens the comic book drawings projected behind us requires me to stretch a lot.

“We will try to give you a little more room,” the dresser promises.

This seems to be the theme.

The swastika is especially vivid against the bright green of the SS Officer costume. But in this first big league production of The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (it premiered at Indiana University on talented undergrads last fall), the takedown of three Nazi avatars in 20 seconds of kickass by the eponymous characters’ Jewish paragon__the Escapist__is epic.

Jerimy, who also fights the supersuit and its lack of potty ease, is ecstatic. I have been an available ear for him since he was a teen, so he is candid with me about this casting.

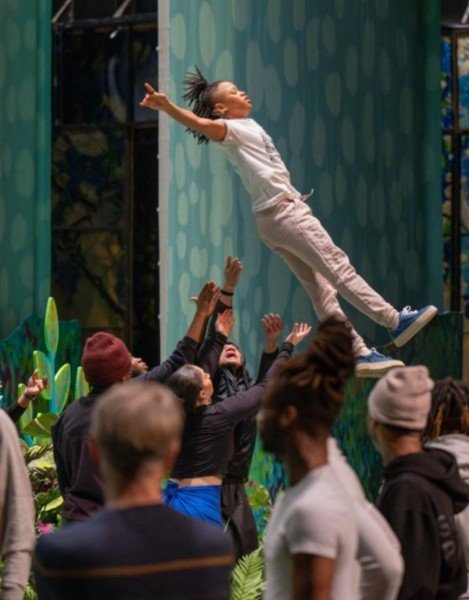

“I don’t think they can imagine,” he tells me, “what it feels like for me to play a superhero on stage. It’s a childhood dream come true.”

Of course.

Jerimy, a Puerto Rican artist who is obnoxiously capable of most things beyond his extensive classical and hip hop dance training, often gets passed over for his white counterparts. He is a real action figure. That he was singled out based on talent and stunt level skill as the clear choice for a Jewish superhero in an institution built on exclusivity is noteworthy.

And I heard there were definitive notes from higher up that Kavalier and Clay needed all the Woosh! Bam! Splat! that the building could muster from its roster. The meritocracy swung my way as well—the original plan was for there to be three Escapists. When the creative team revised to one but still wanted a bona fide Marvel-worthy fight, I became the villain, afro notwithstanding.

To be clear the Met has a track record of yielding to greatness when it has to. They applauded Leontyne for 46 minutes. And I heard Kathleen at the Met earlier this year.

Now I get to die a Puccini-level death in a fraction of the time at the hands of a Jewish hero who prevails over Hitler? Yeah, that works for me.

Because I internally cover Jerimy as well, my Escapist suit is further along in feel and functionality than my SS garb.

“Can we review this change before the knockout?” I ask him.

“Sure,” he says.

We do. Then we stand on stage waiting in the tech delay. We hear our choreographer Mandy and her associate (the real heroes of the production) in the house weighing in.

“Do you think this opera will make it to Saudi Arabia?” Jerimy asks.

It’s a good question. Amidst the struggle to find space backstage for desks, guns, chalkboards, and a few set pieces in this massive opera, there is talk of the recent multi-million dollar deal with Saudi Arabia that will rescue the Metropolitan Opera from operational budgeting woes. It will inject enough resources to heal the pandemic gash and keep the Met Opera’s parts tuned. The questions meander around the building in varied resonances—is the cultural exchange of any real interest or is it just the cost of doing business? Is the premier over there shifting the dynamic for women enough for ours to feel safe? Are we past the Khashoggi tragedy or still a little shook?

The eve of our first rehearsal for this opera was the air date for the third season finale of The Gilded Age, where I was able to play a late 19th Century Black aristocrat. I am a little behind in my binge plan to catch up (we shot in January). But I have been edified through dramatization about the “new money” spite that birthed this juggernaut nonprofit while working in its Lincoln Center house. I am reminded how far the Met has come in terms of diversity, even with the tacet (yet clarion) vibe throughout the building that any interest in real inclusion is strategic, not earnest.

I’ve not met enough above-the-line folk to know for sure. But it sure is ironic that extremely wealthy brown people in the Middle East have extended their capes.

The good news is that if a Puerto Rican man and a black man are entrusted in this opera house to tell a portion of a Holocaust narrative based on our skillset (and perhaps because we know something about the impact of hatred), we can move at least a centimeter toward everybody getting there.

“I’m not sure,” I say. “But the part where we make out in Act II could be problematic over there.”

The male singers and dancers got an intimacy coordinator for this.

“We will sell out here though, for Cardi B alone.”

Jerimy smiles, knowing whom to blame for her involvement.