She likes long hair.

In fact, in every iteration of every Cher concert I have ever performed in, she insisted that I grow mine out. Before D2K, as was the case with our three-year stint at Caesar’s Palace, I had just come from a Broadway show whose period conventions (and headwear) made it necessary to start my tresses from next to nothing.

But she wanted them long anyway, unbothered by the degree to which my unruly hair kinked and curled on to itself through its torturous in-between stage. And on me, a very fair-skinned dancer otherwise difficult to distinguish as black under lighting, my hair always tells the story. In an afro, out and free, or in cornrows, it screams my heritage loud and proud.

So I am disheartened to know that racism is part of the charge leveled in a lawsuit at my boss. To read in various news outlets that the quality of the racism is so specific, that skin color is the platform, is baffling. First, there is my general irritation with the quite trite marginalization that happens when a darker brother or sister, or anyone else really, discounts me (and in this case, a caramel female counterpart still employed on the tour) in the conversation about blackness. But even if there is some shred of merit here, the lack of consideration for the three brown band members (of which there are only seven) still in Cher's camp befuddles me.

In fact, one of the most interesting experiences I’ve had dealing with the color quota represented on stage happened on Cher’s stage in Vegas years ago. A brunette out for her wedding was replaced by the cousin of another black dancer on the gig. Adding two of the plaintiffs (who were also there) brought the count of bona fide chocolate up to four, and then there were the two of us too light to figure in. Among the other six dancers were a Latino and a Tongan, both with enough pigment to type them out of a Mayflower Voyage film. We didn’t know whether to take a picture (because who would believe it) or accuse our boss of Blaxploitation. Because of course there were also the two black backup singers, the keyboardist and the drummer…

This doesn’t happen with a racist performer.

In fact, since my first gig with Cher twelve years ago, I have missed only 2 of her 568 full stage shows. Never in any of them have I experienced any form of racial or sexist prejudice.

It’s not her style. I was there every time she strutted around stage in a Native American feathered headdress singing about her Cherokee heritage. Early in a career older than all of her dancers, she was notorious for entering the back door of venues and restaurants that would not allow her colored staff through their front. She argued with her fans via Twitter that the Tea Party supports racist policies. She funds the Peace Village School in Kenya for black orphans. And the available dance captain promotion on this tour came to me, not the white guy.

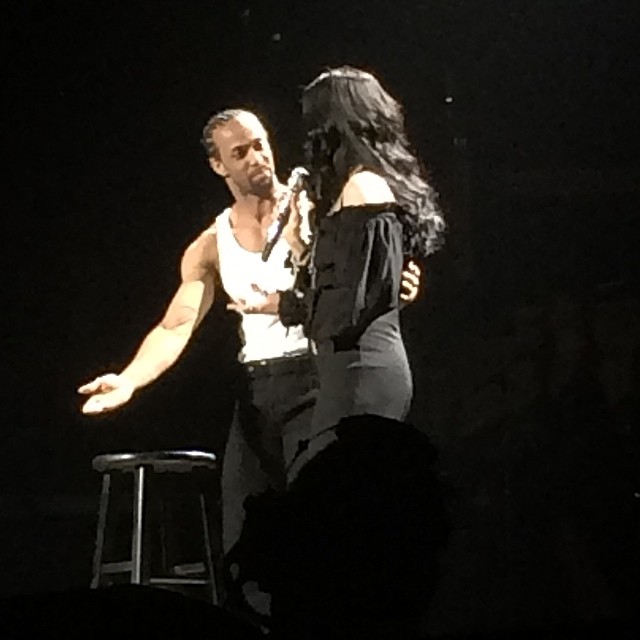

You know, there was a budget for my hair. When I ran out of Mixed Chicks conditioner on the road, or couldn’t find a barber for a manicured fro, Cher reimbursed receipts for cornrows. It did not bother her any when I walked on stage wearing them, black pants and a white tank—a look that might have gotten me shot by police in Ferguson—to stand in her spotlight and present her a stool. This is the conversation we should be having instead, how my "Burlesque" costume with this hairstyle is life-threatening around those who would see a dangerous, uber-sexualized Negro thug.

Cher was simply happy that it was Jamal bringing her the stool.

During a delay in the tech rehearsal for the number “Dressed to Kill,” she sat waiting on the chandelier and smiled at me.

“I’m getting a weave,” I told her.

“Really??!!” she said, ecstatic.

I laughed uproariously. Although if she finds out about my hair cut I might need a weave… (don’t tell her ;-)